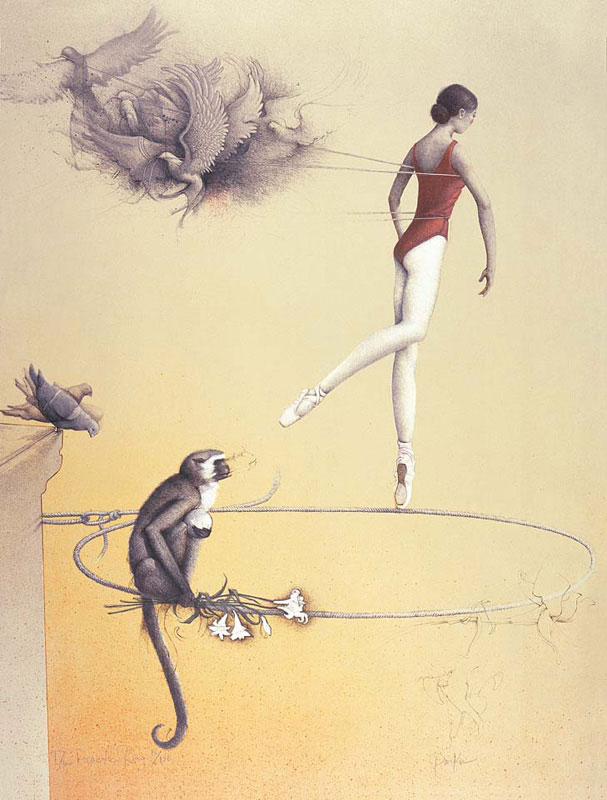

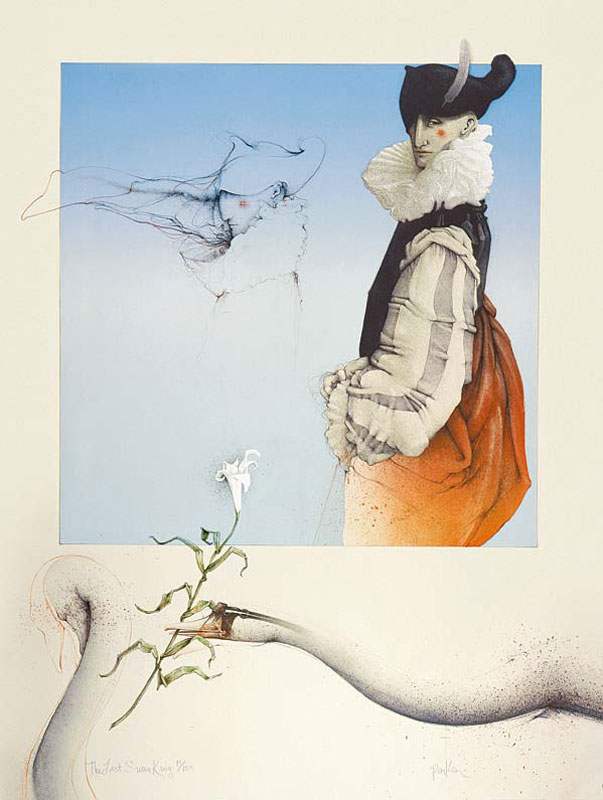

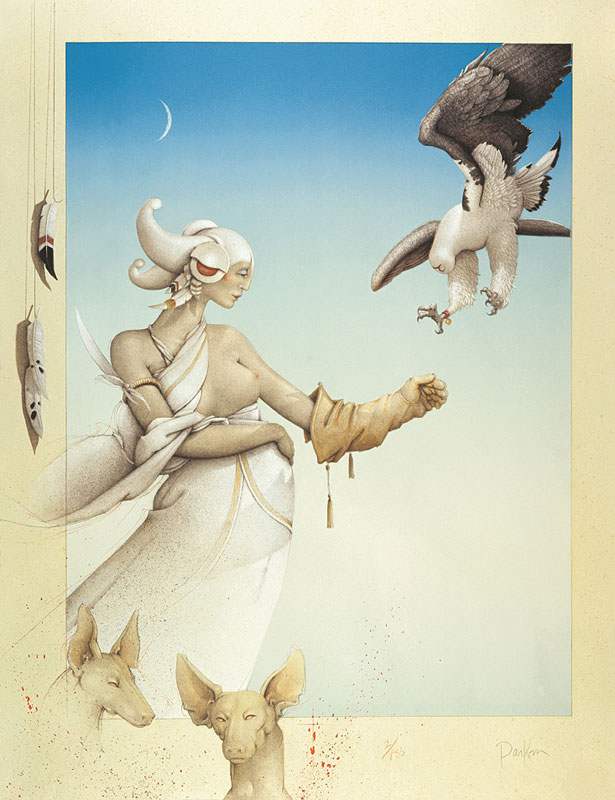

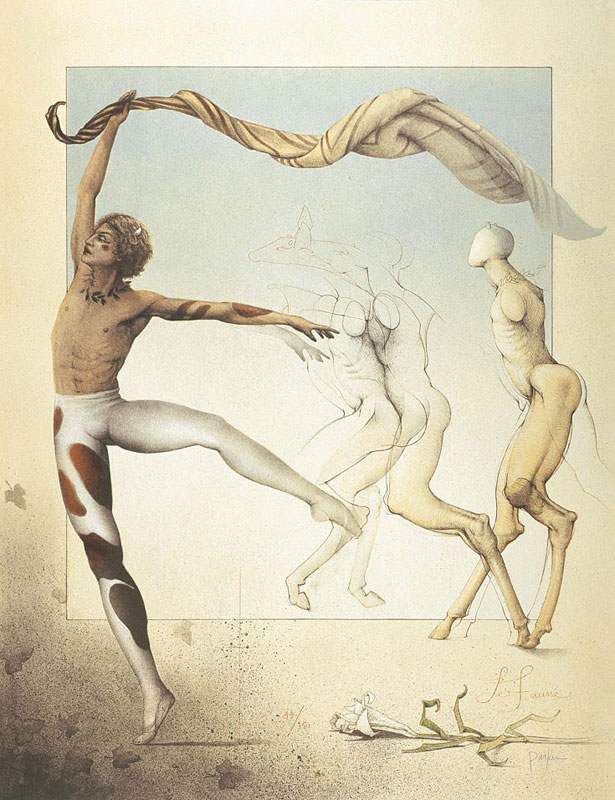

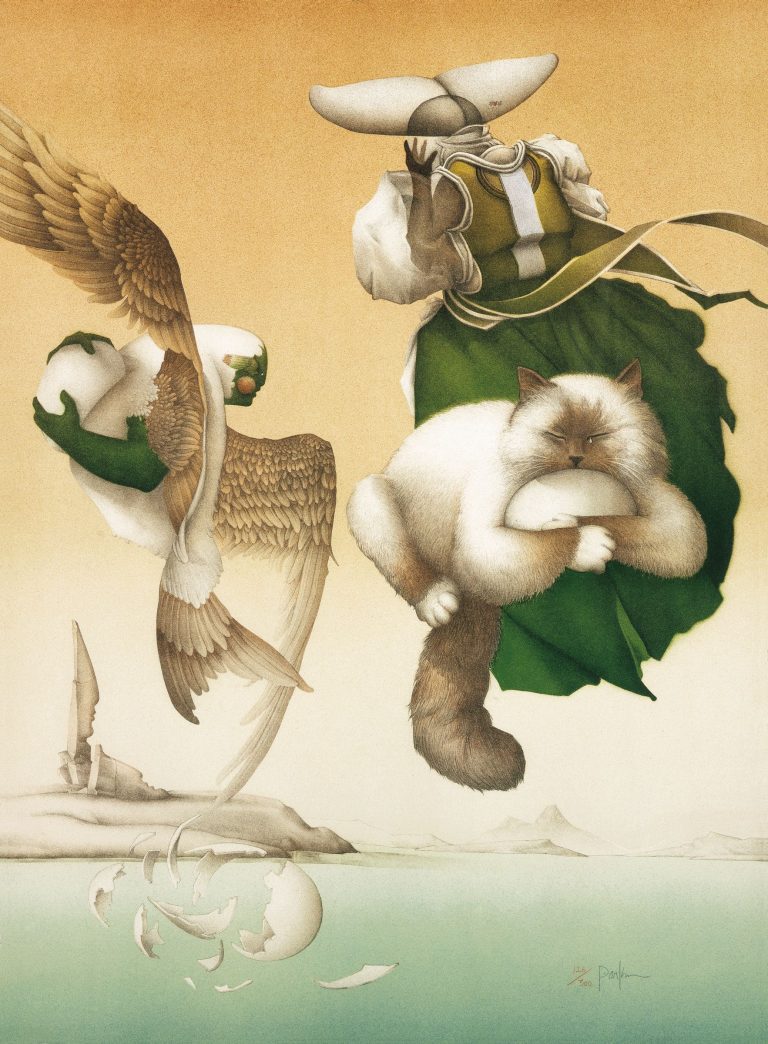

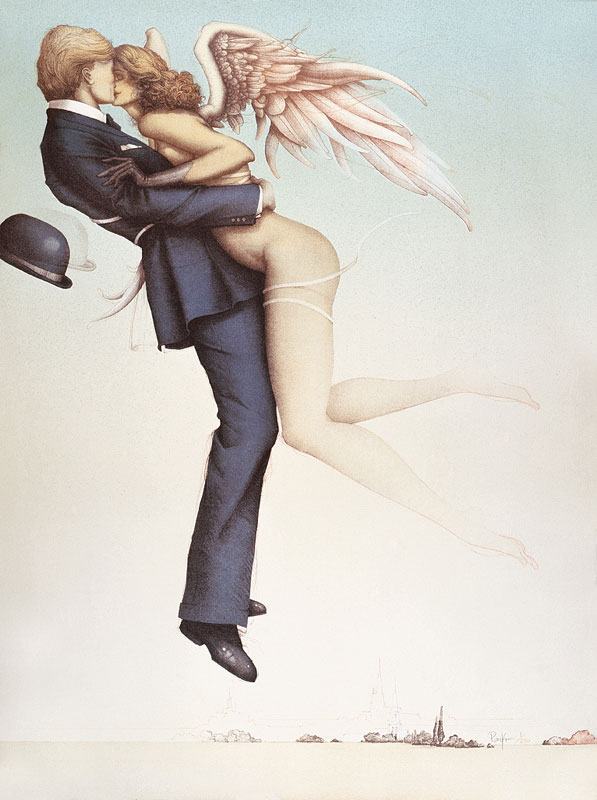

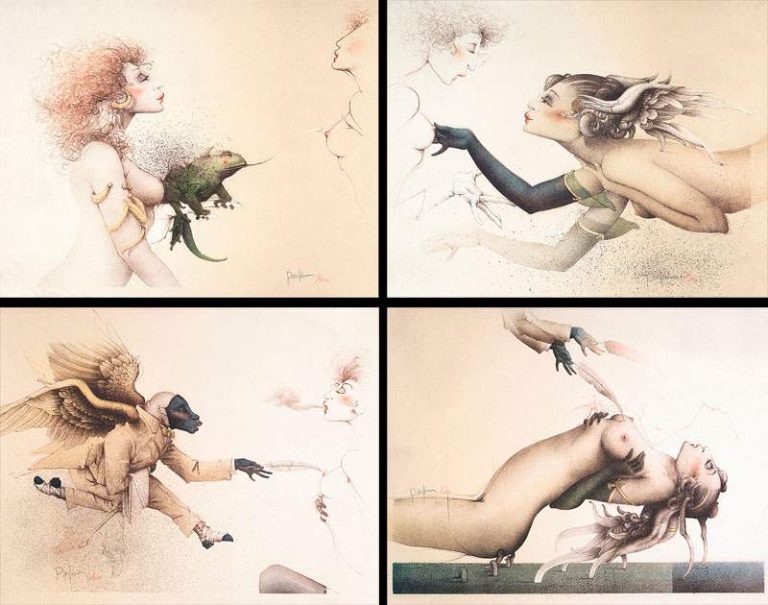

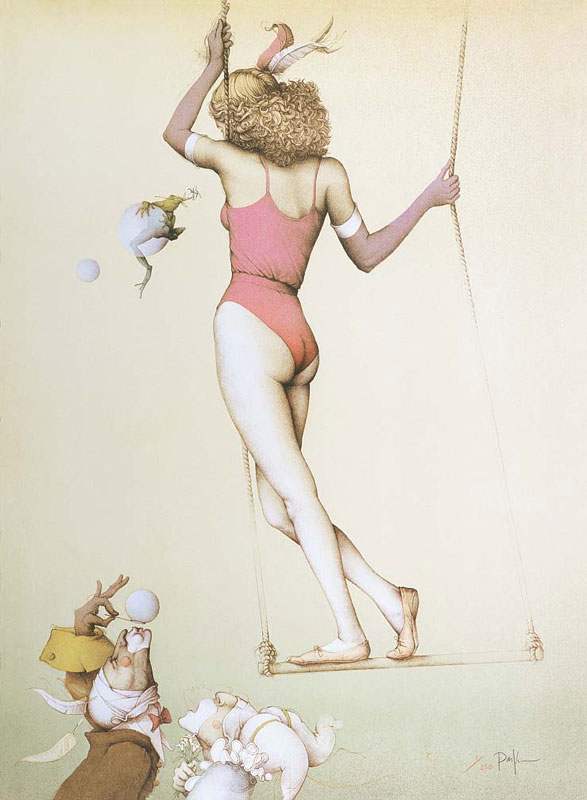

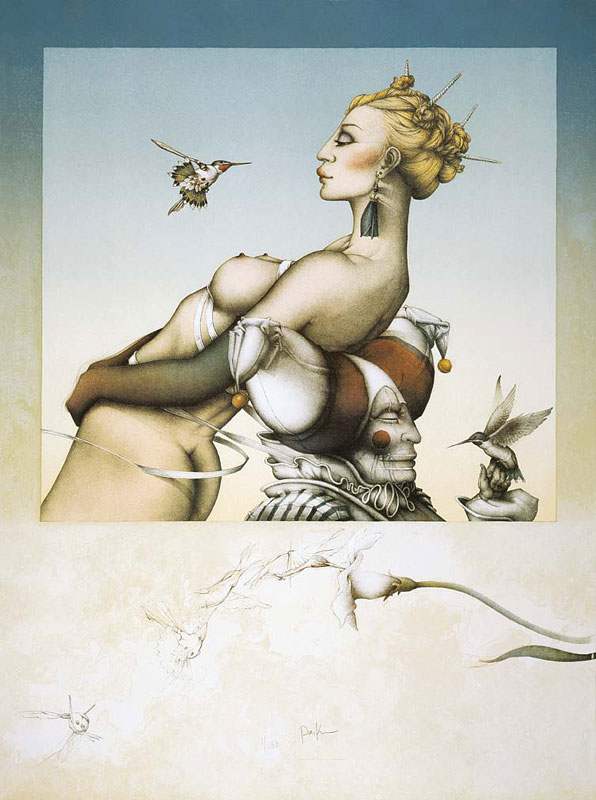

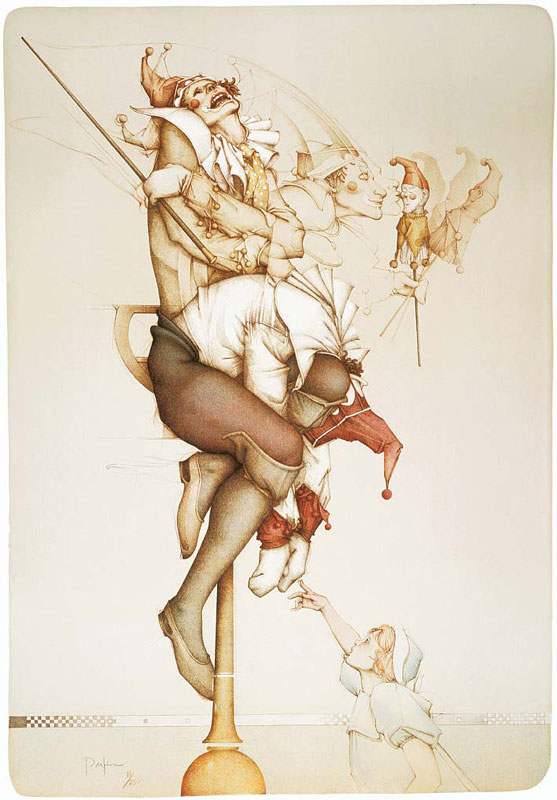

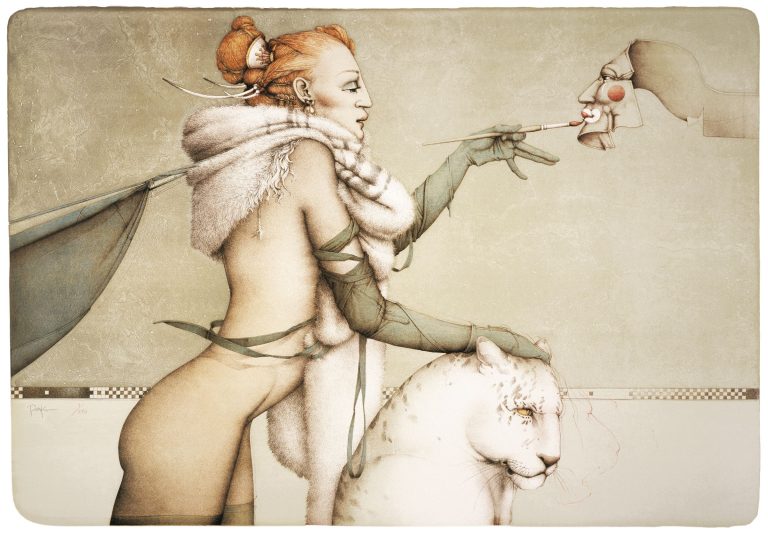

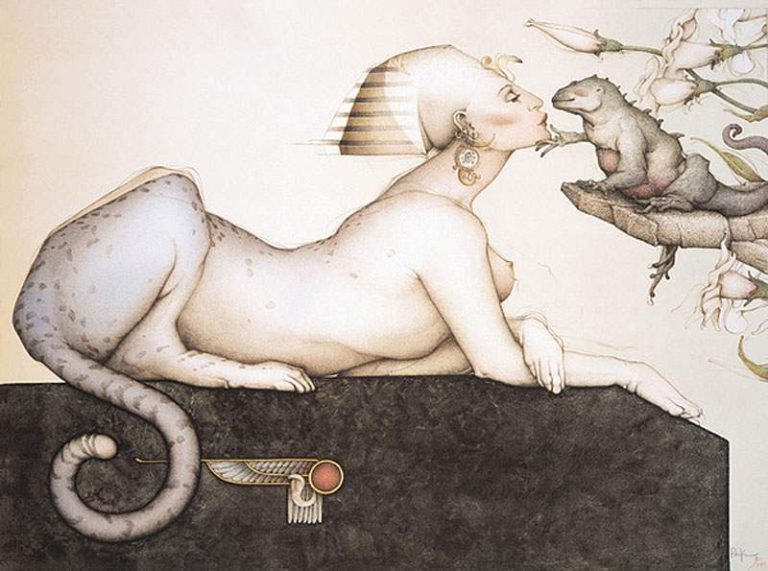

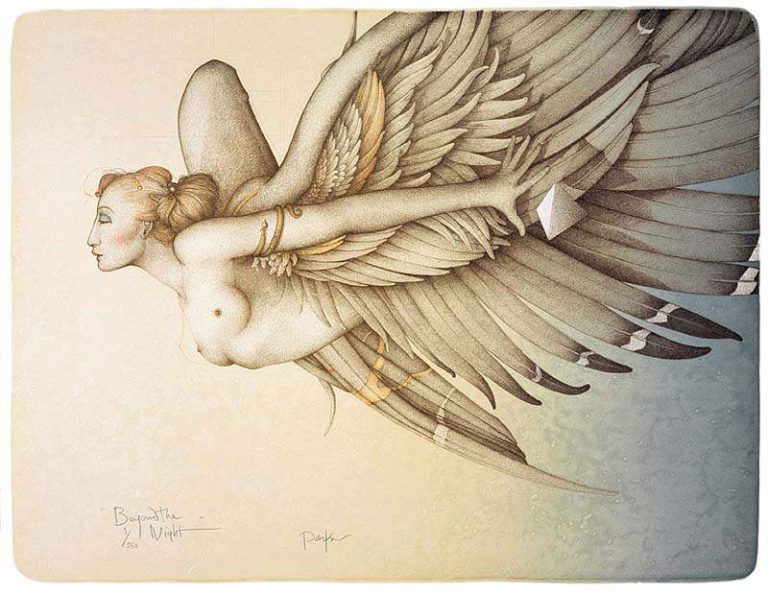

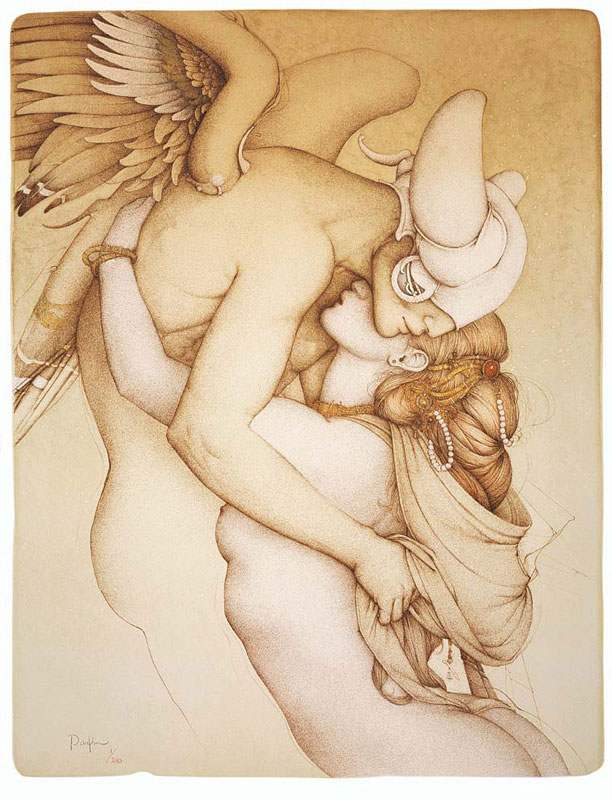

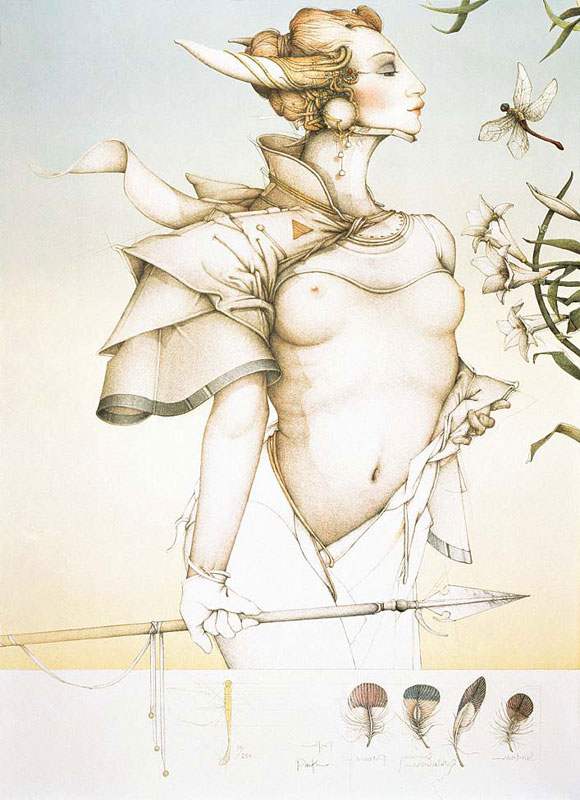

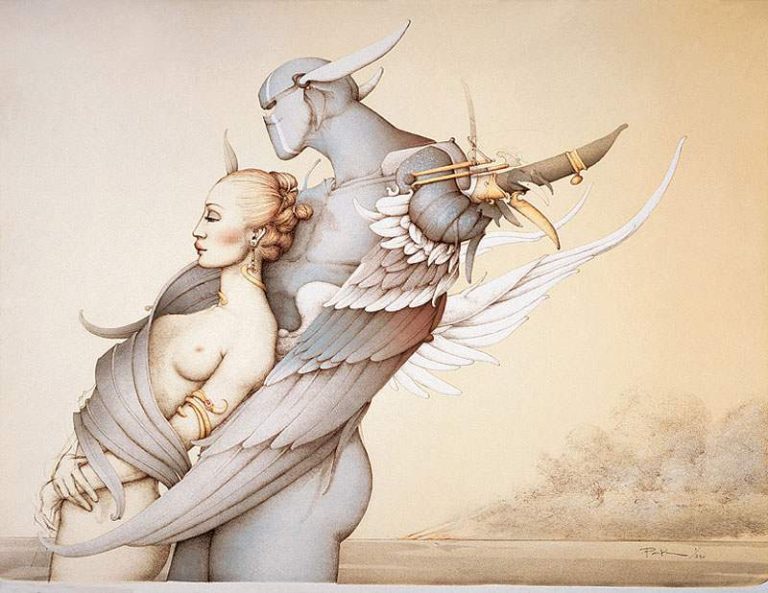

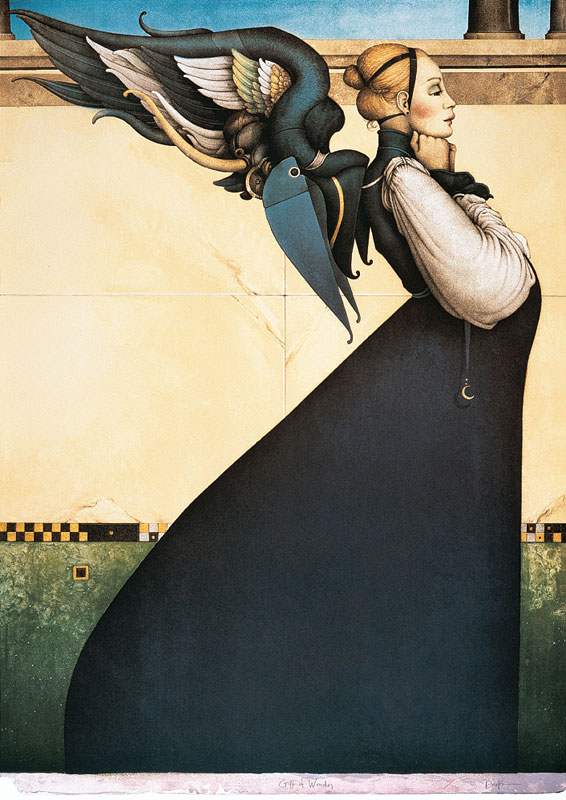

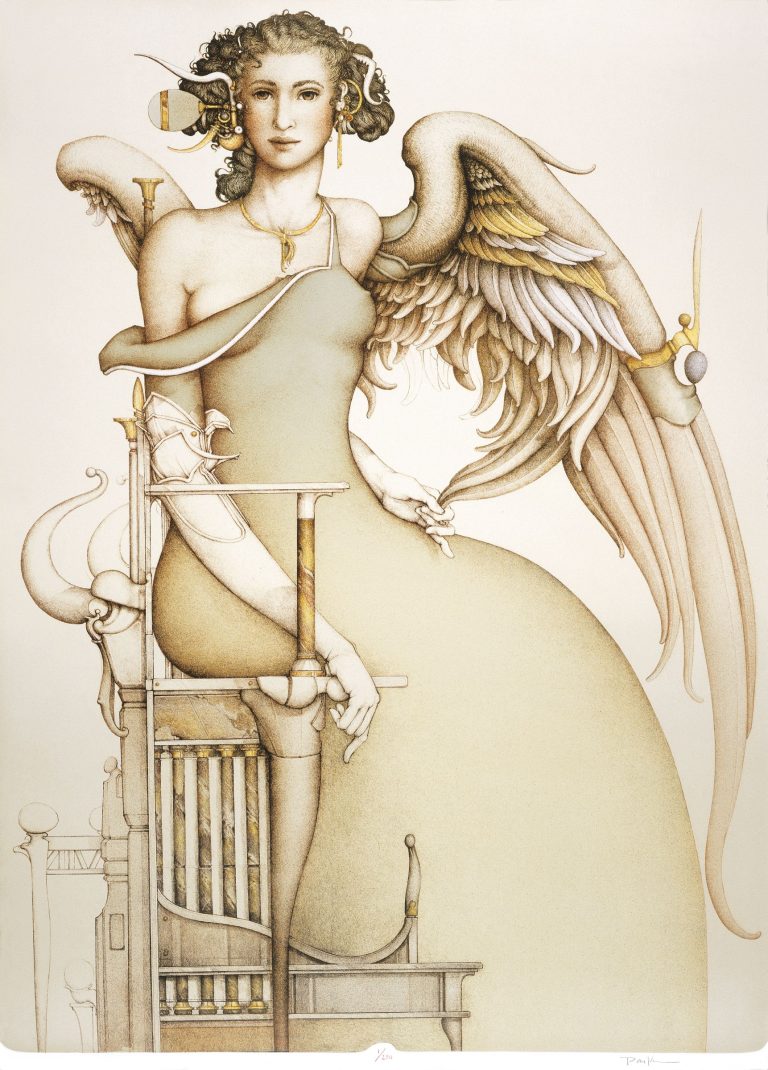

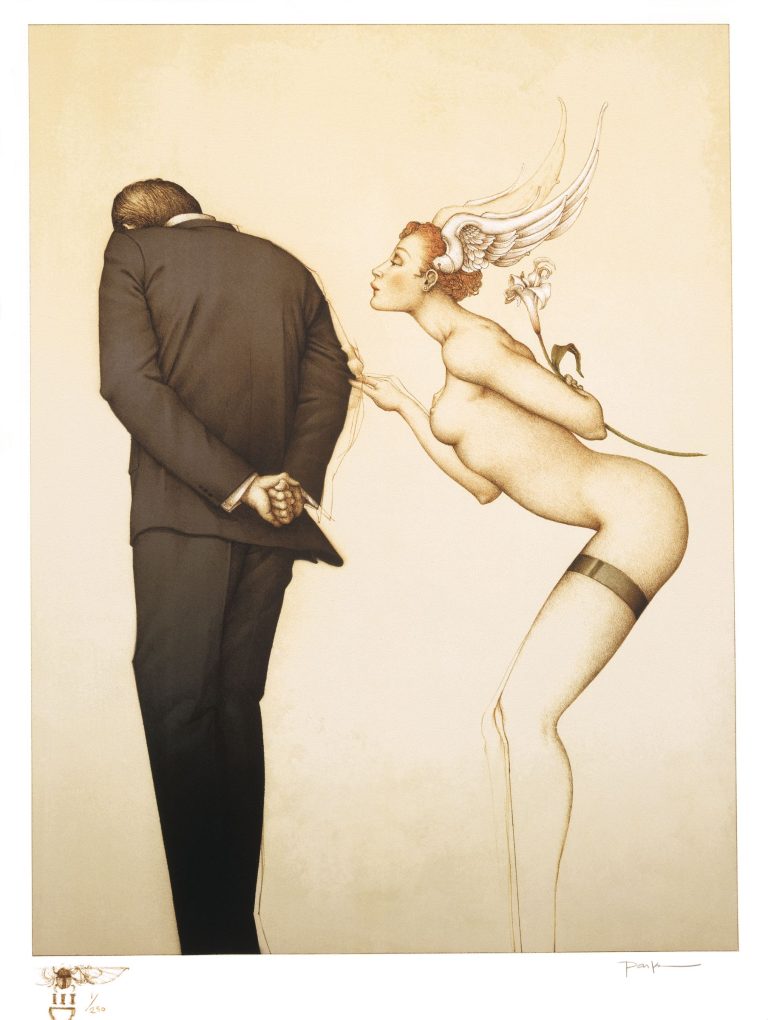

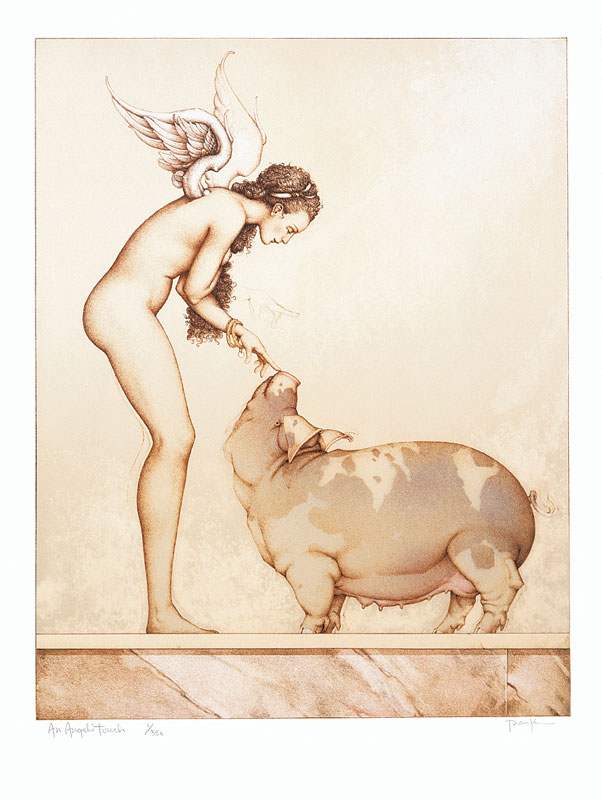

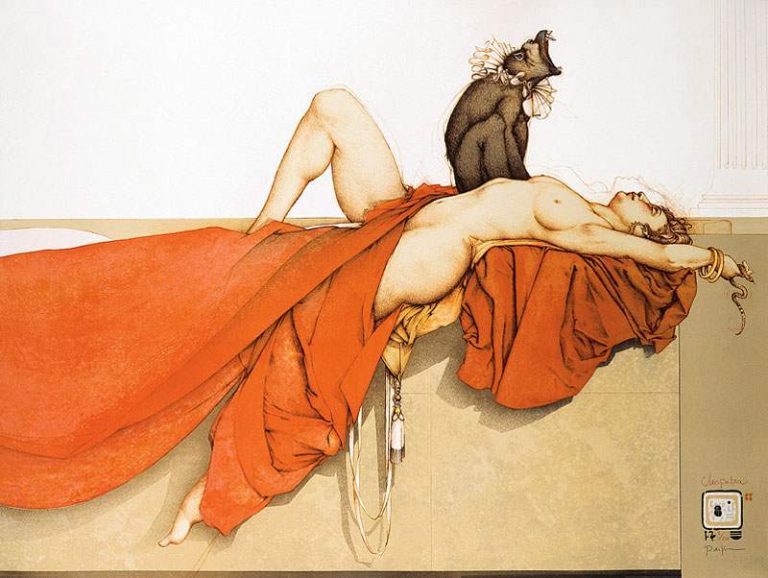

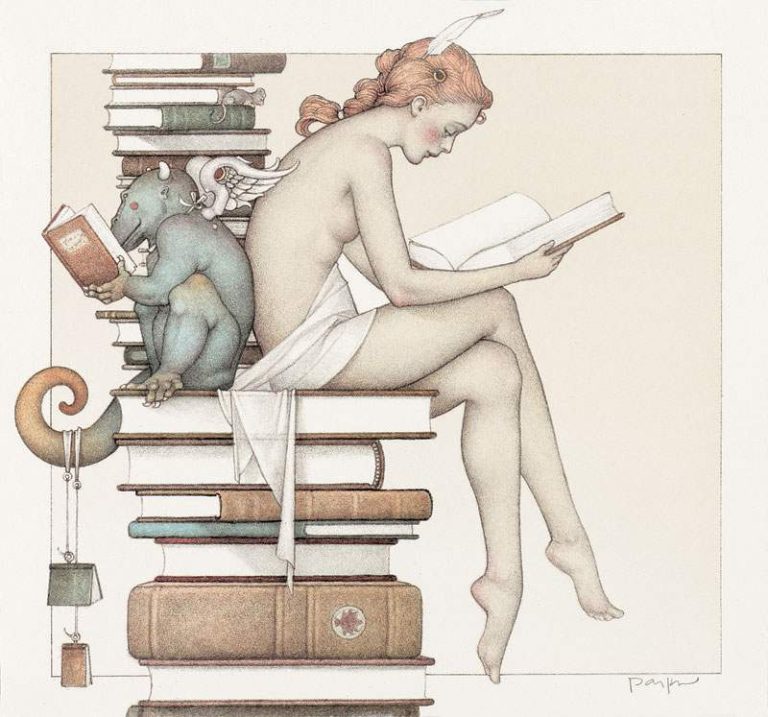

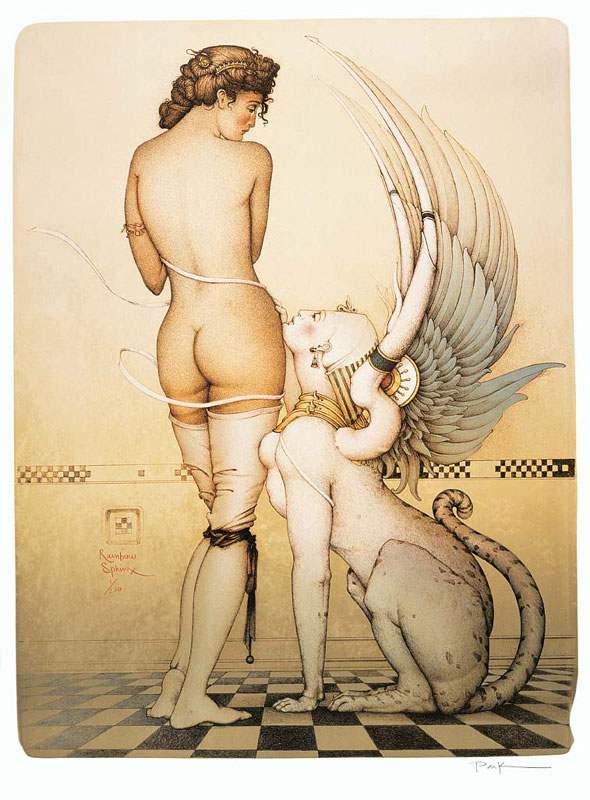

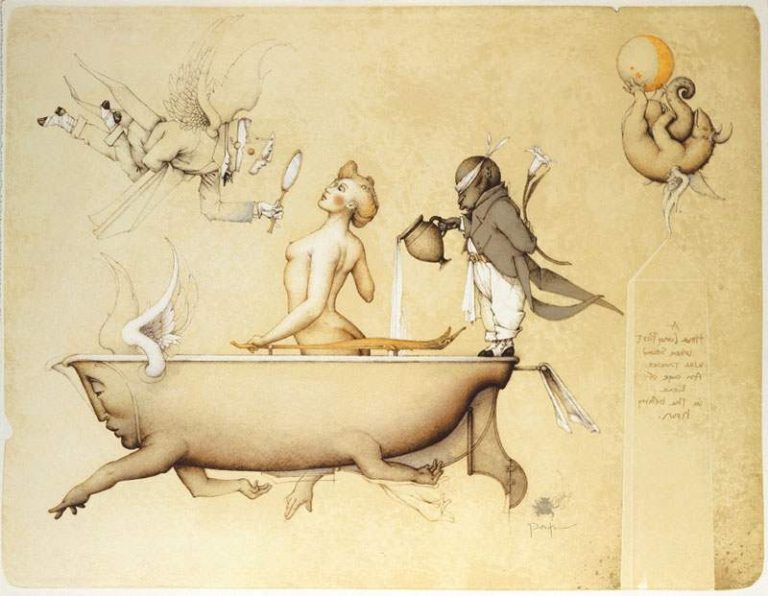

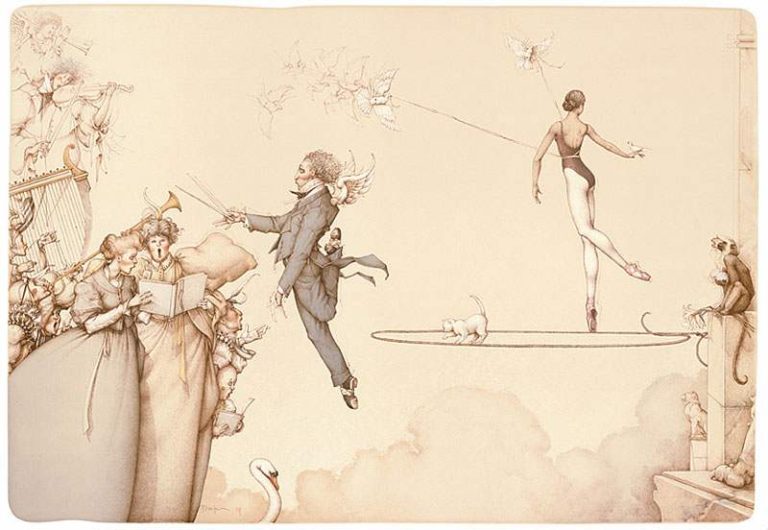

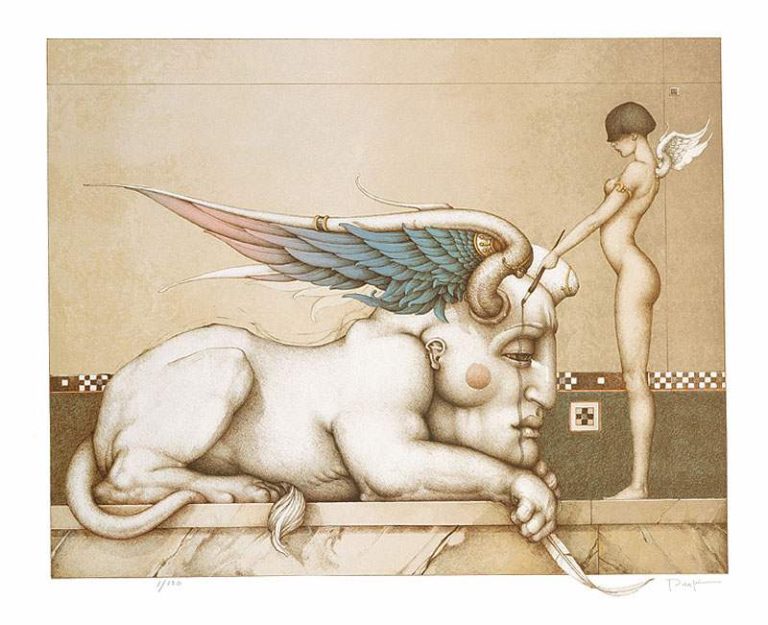

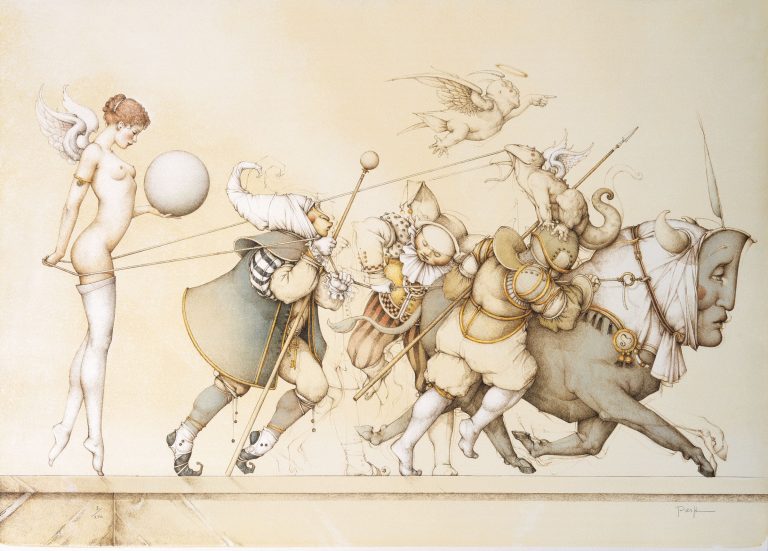

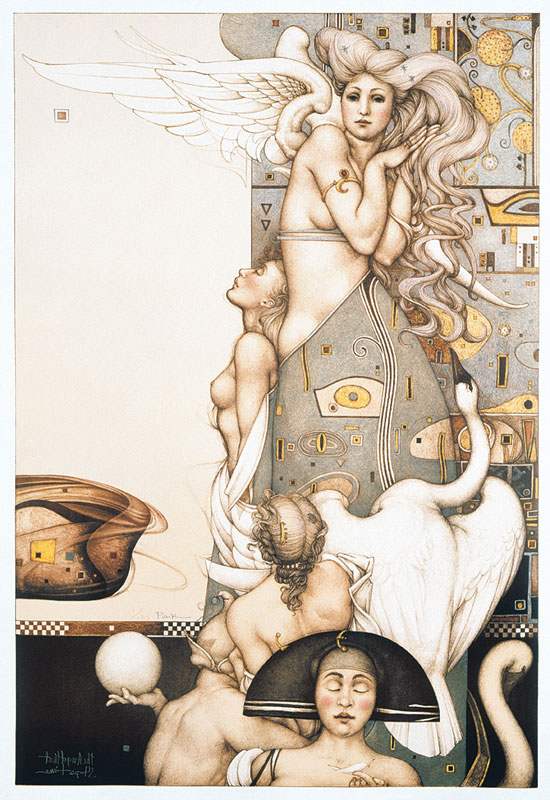

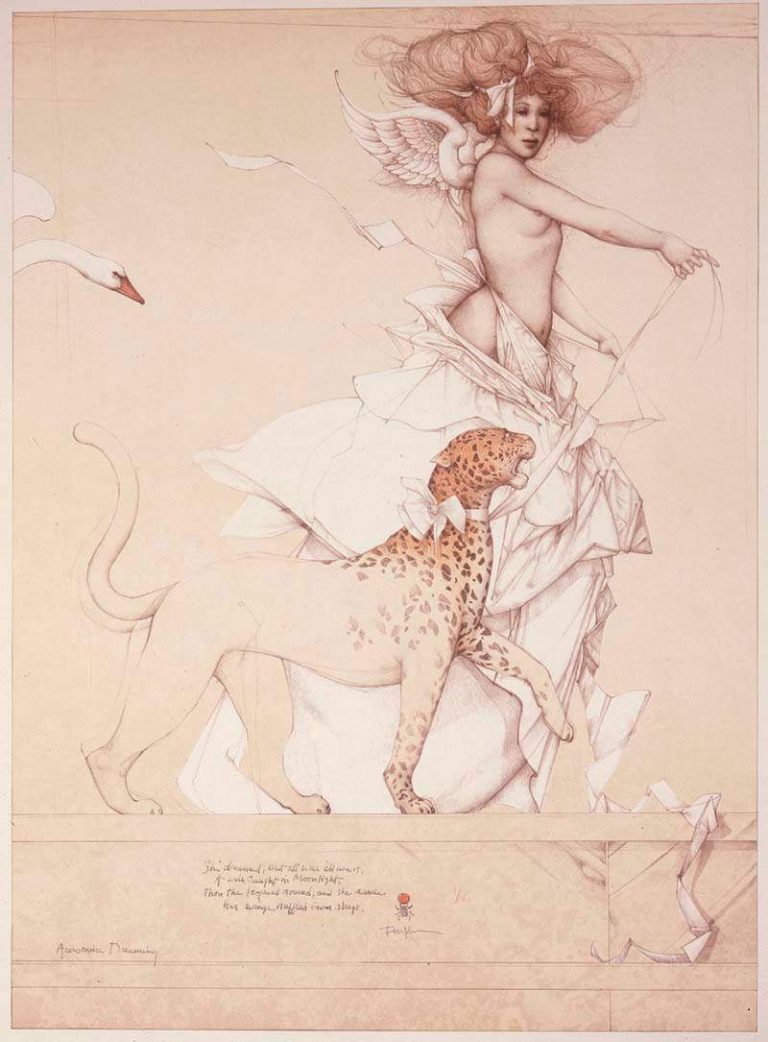

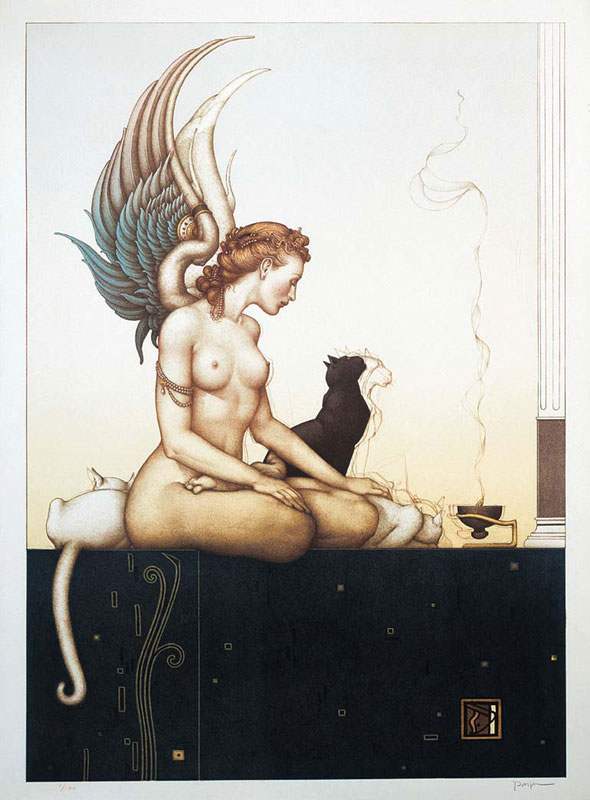

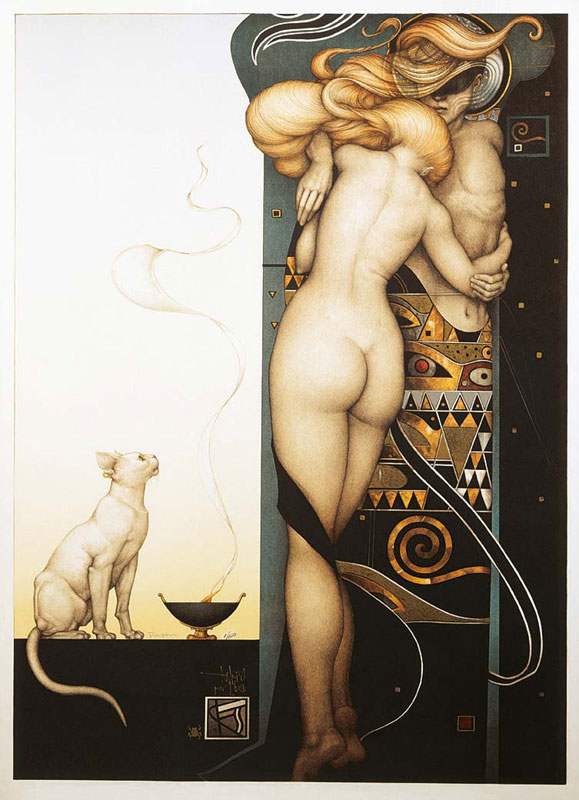

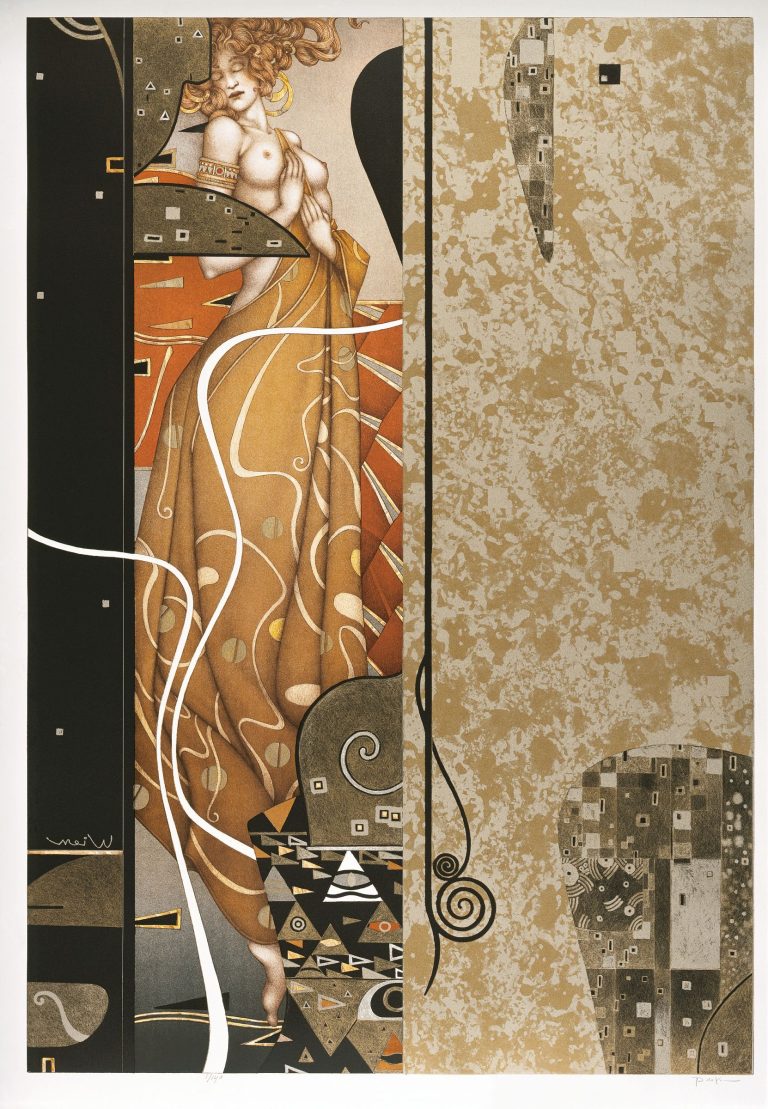

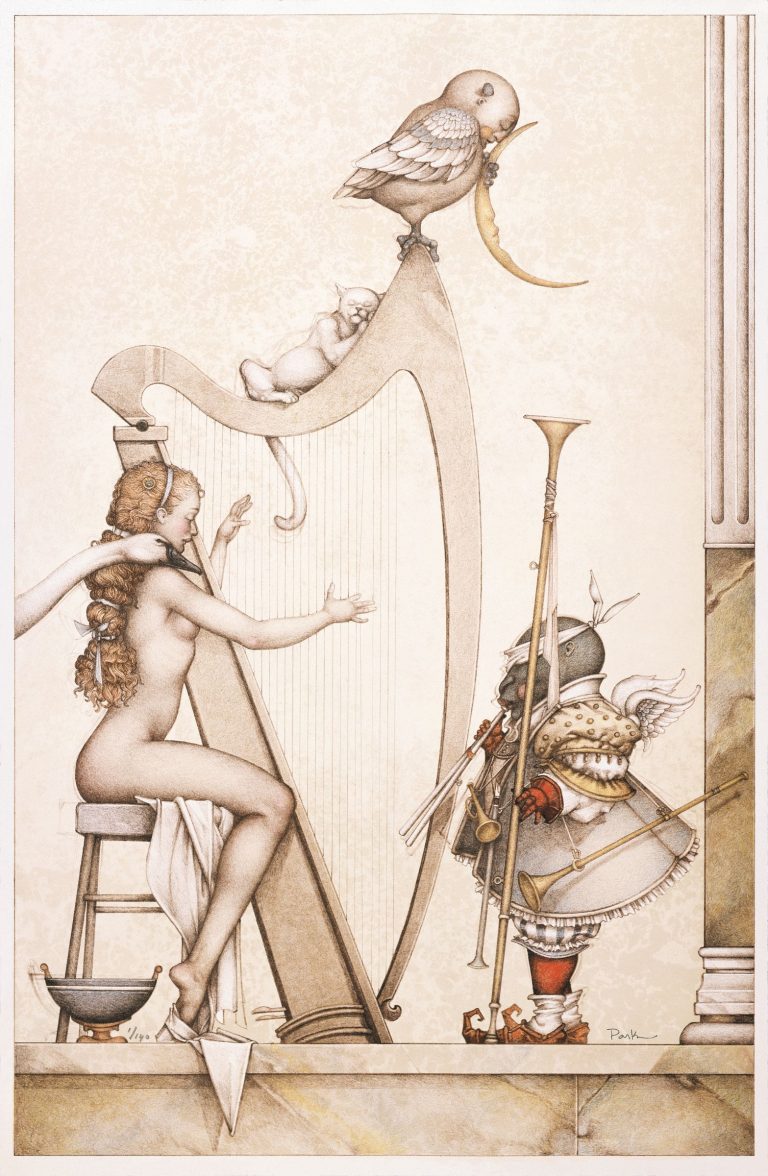

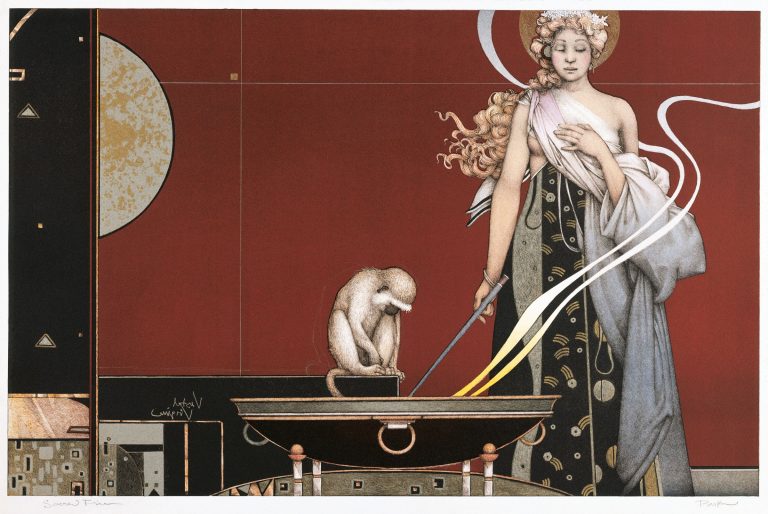

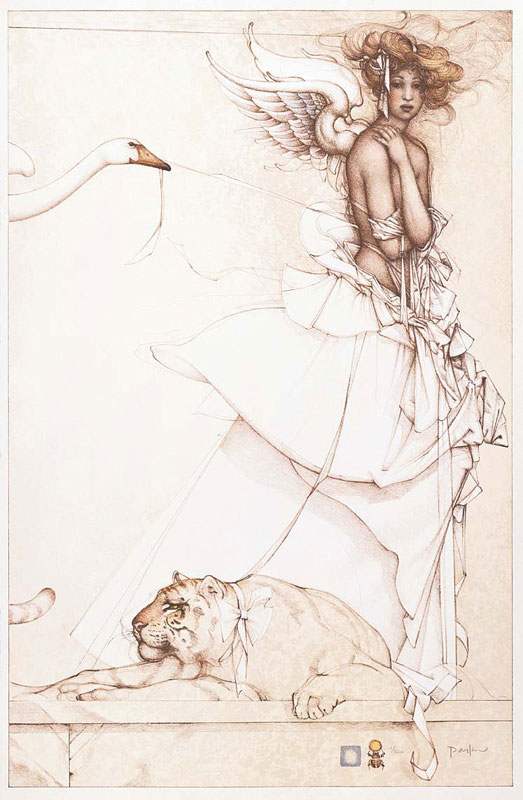

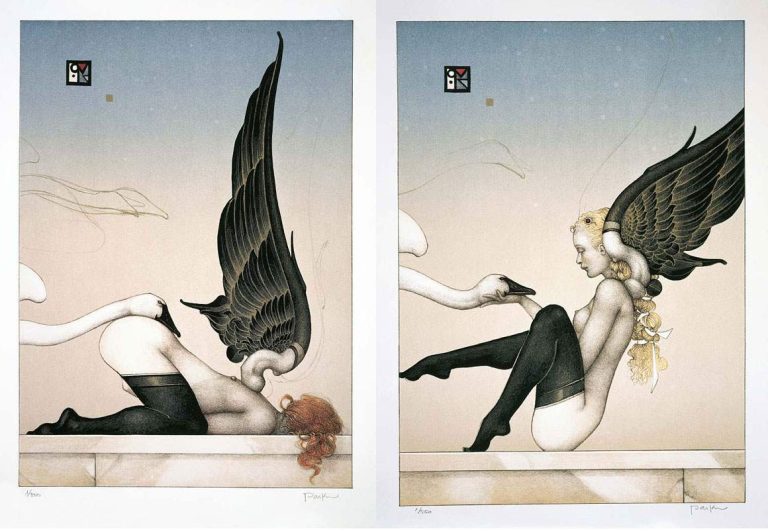

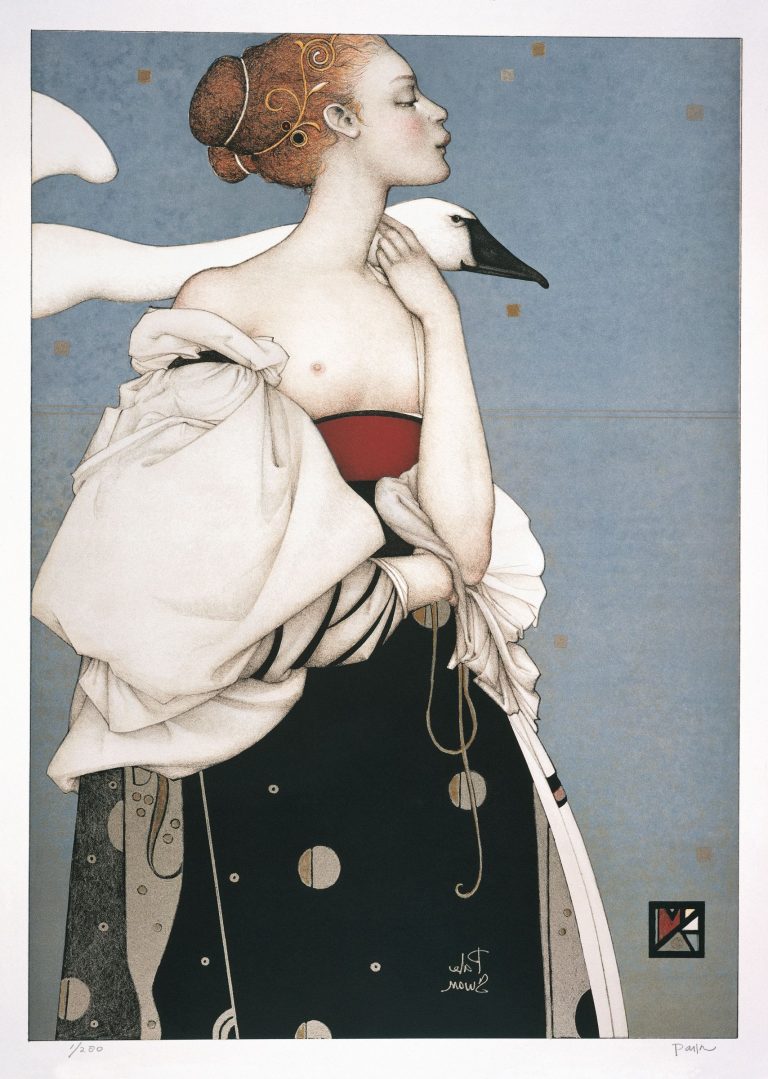

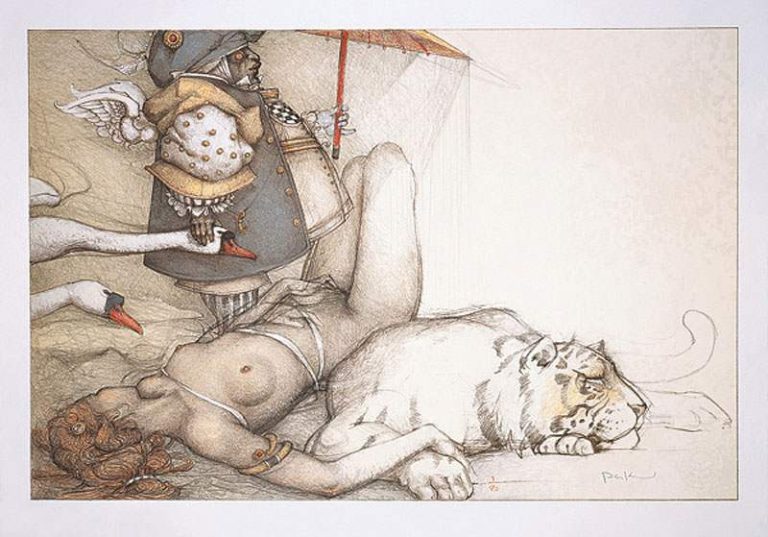

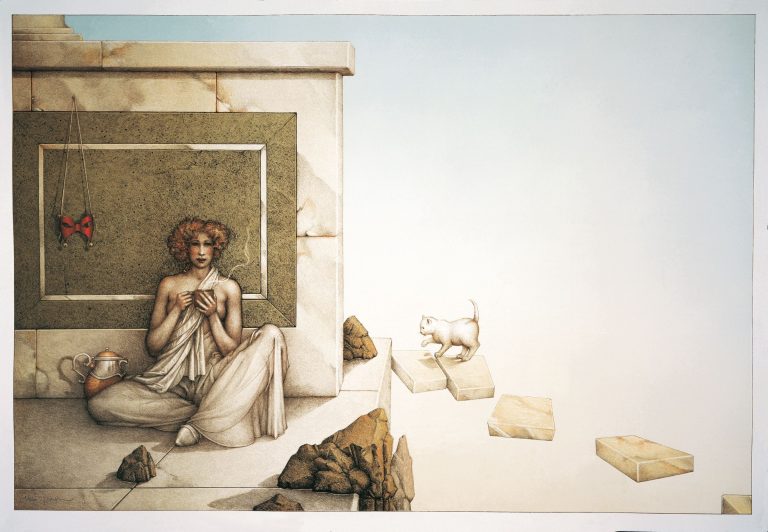

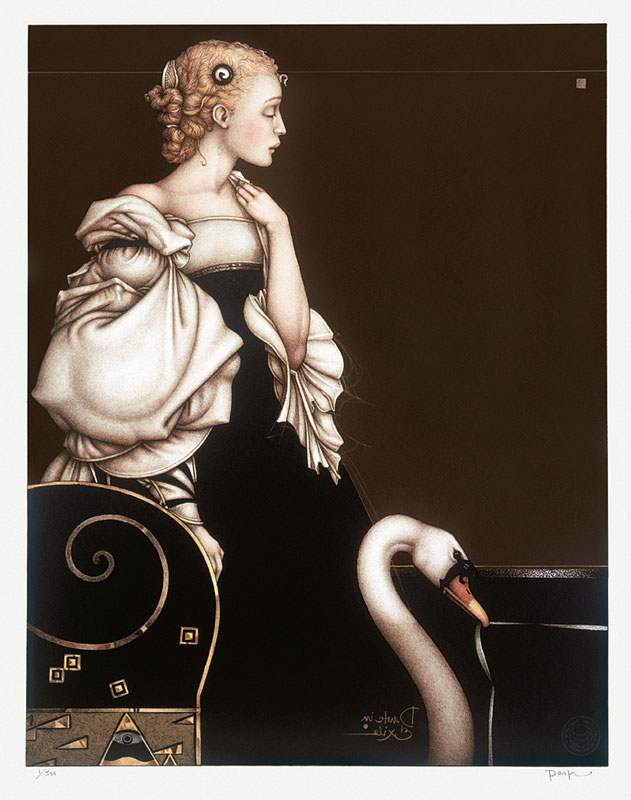

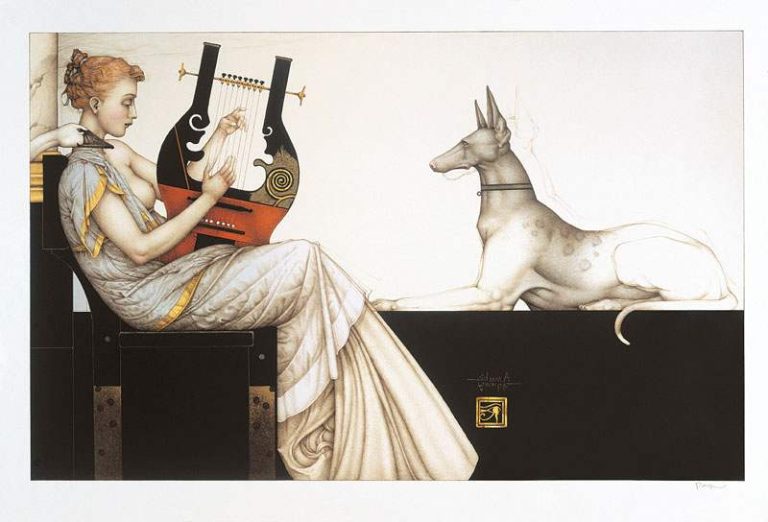

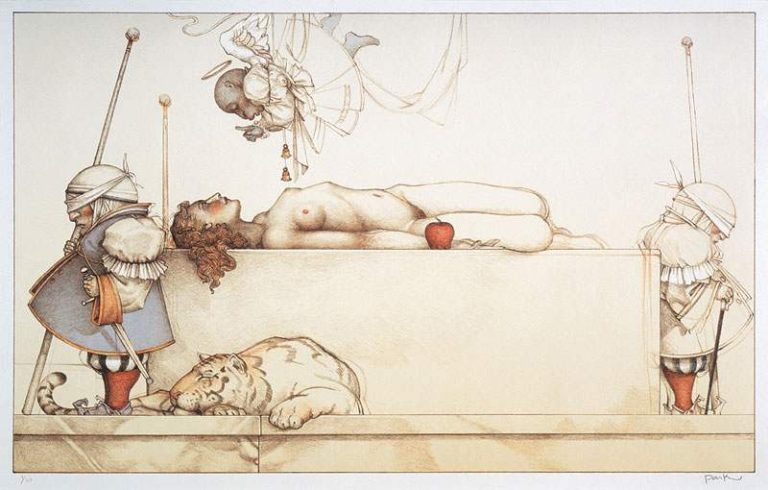

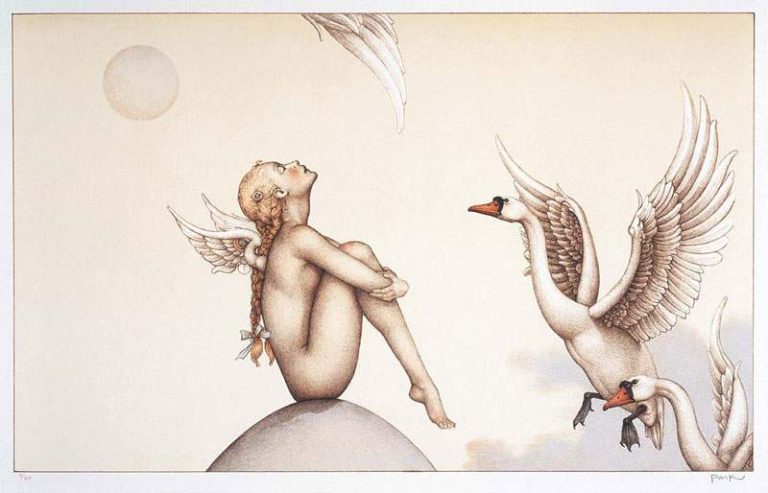

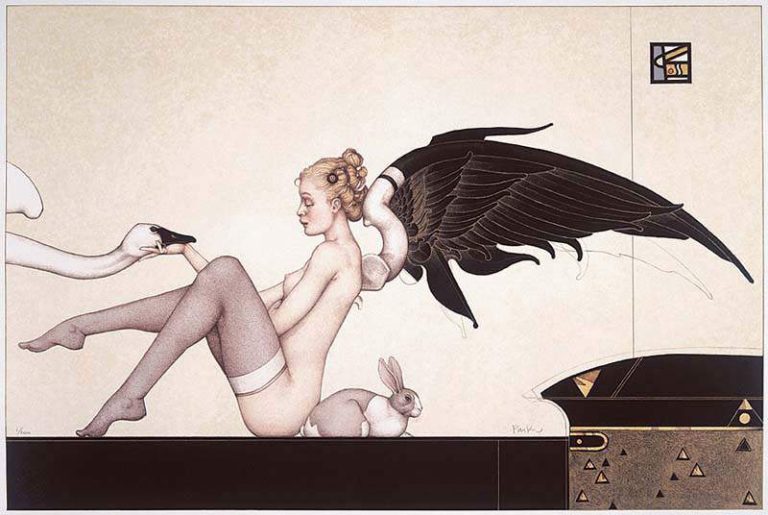

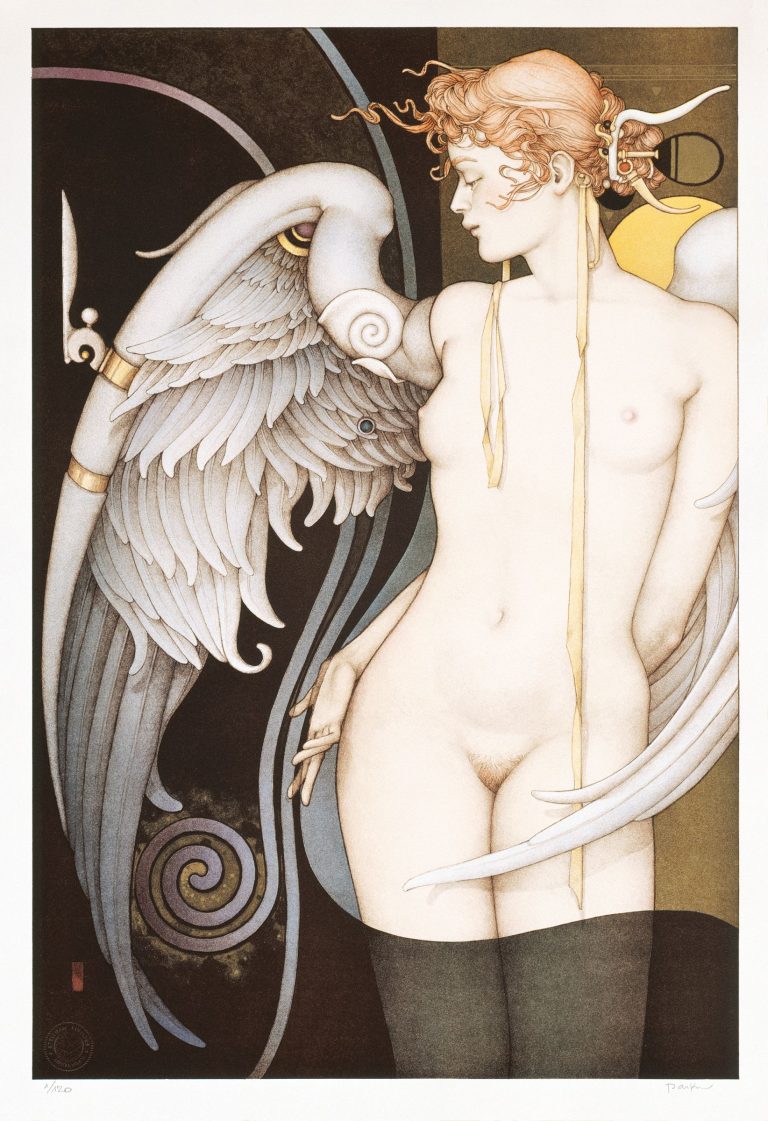

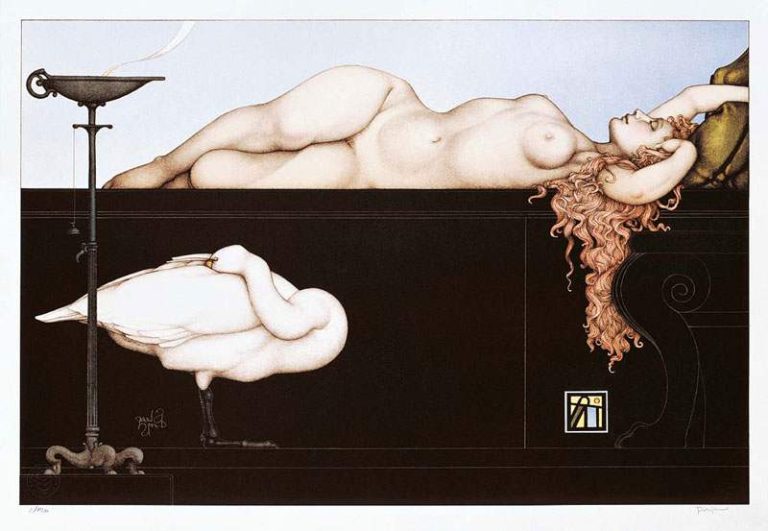

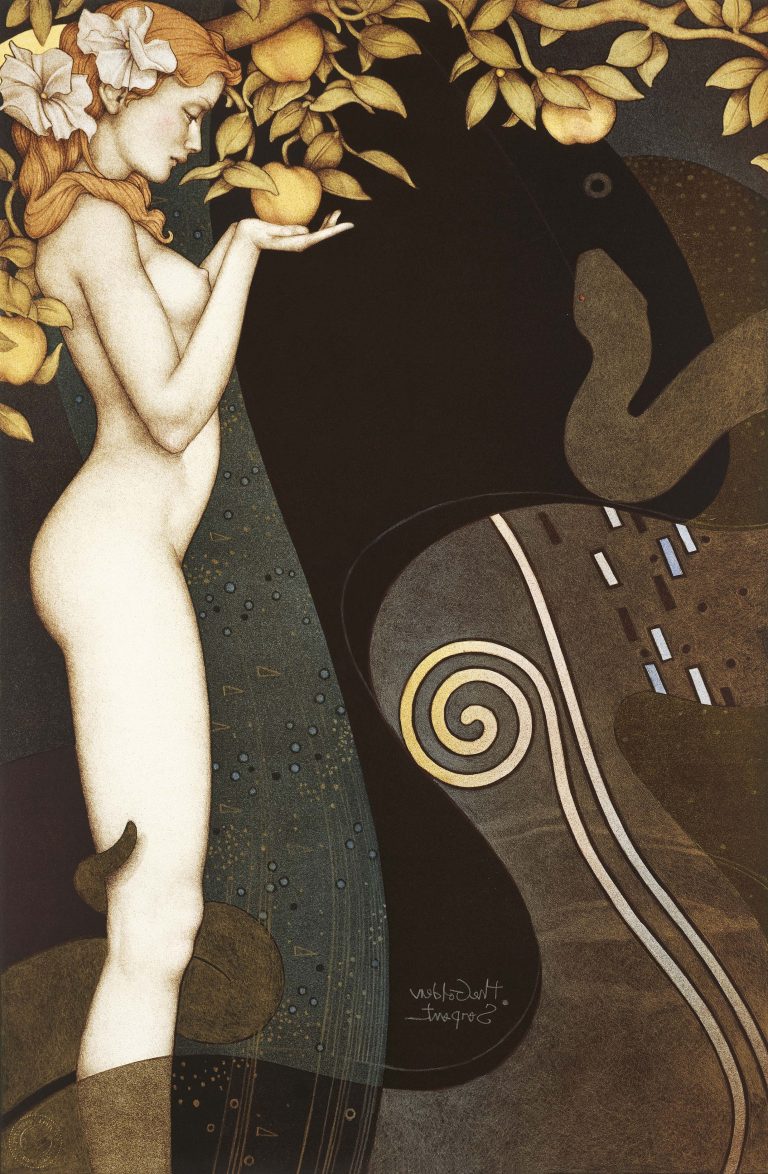

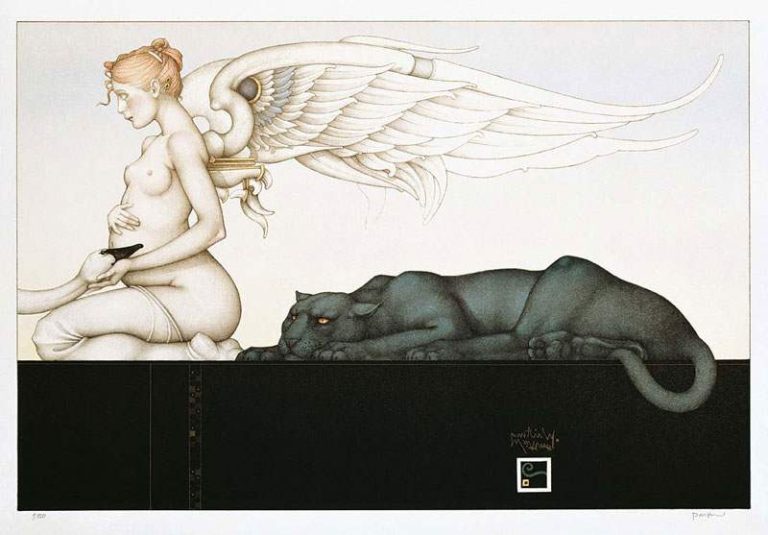

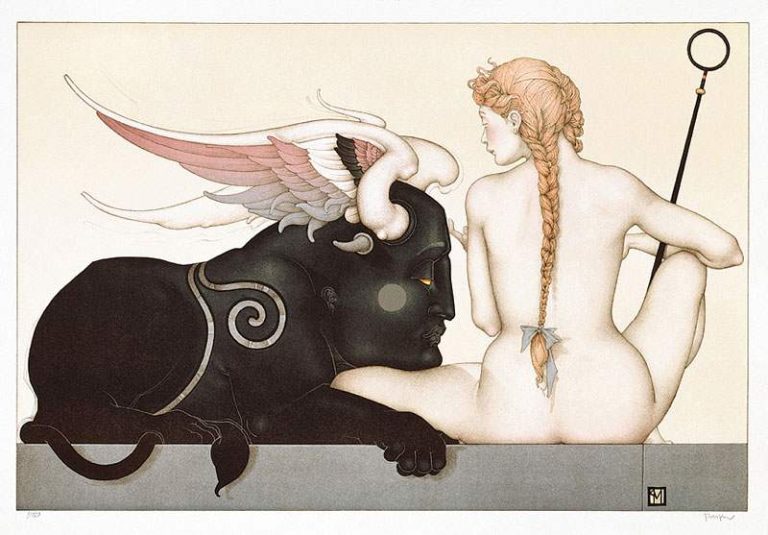

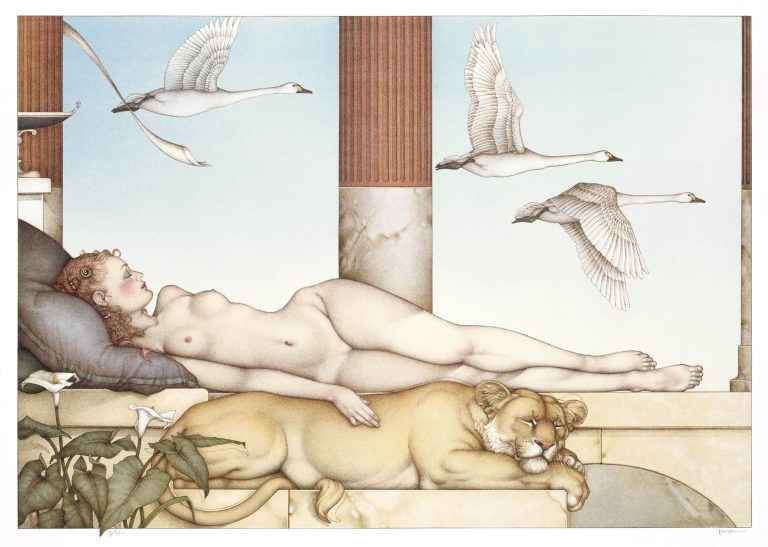

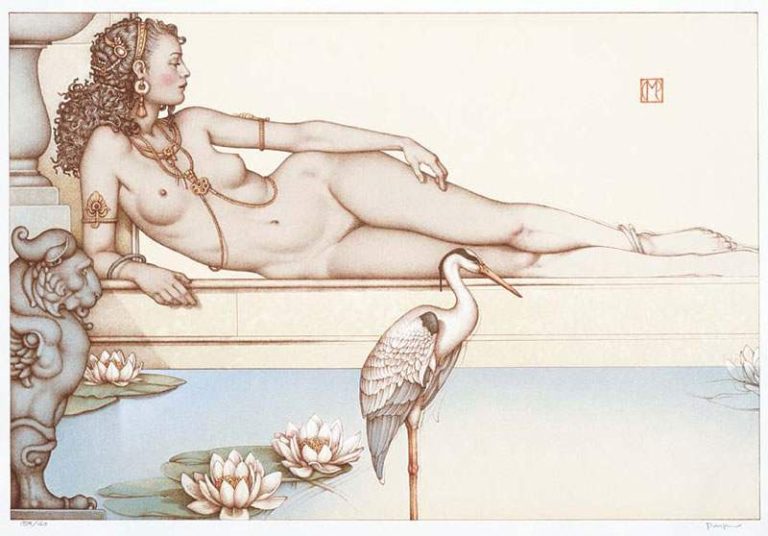

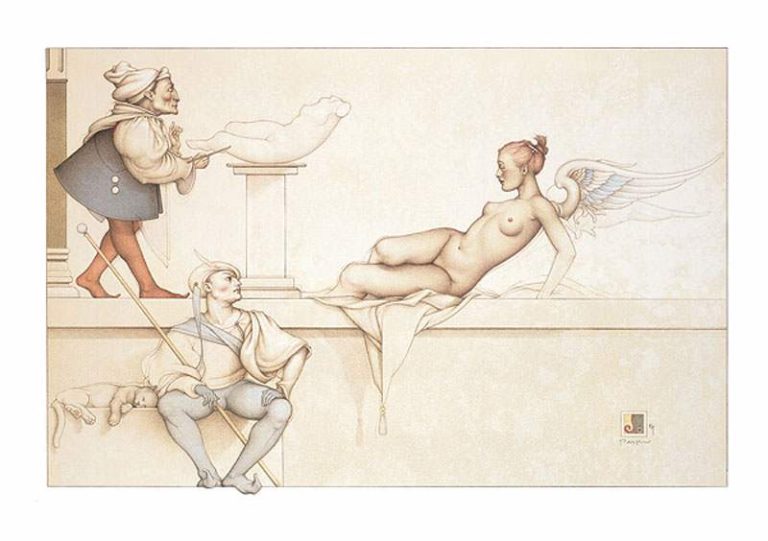

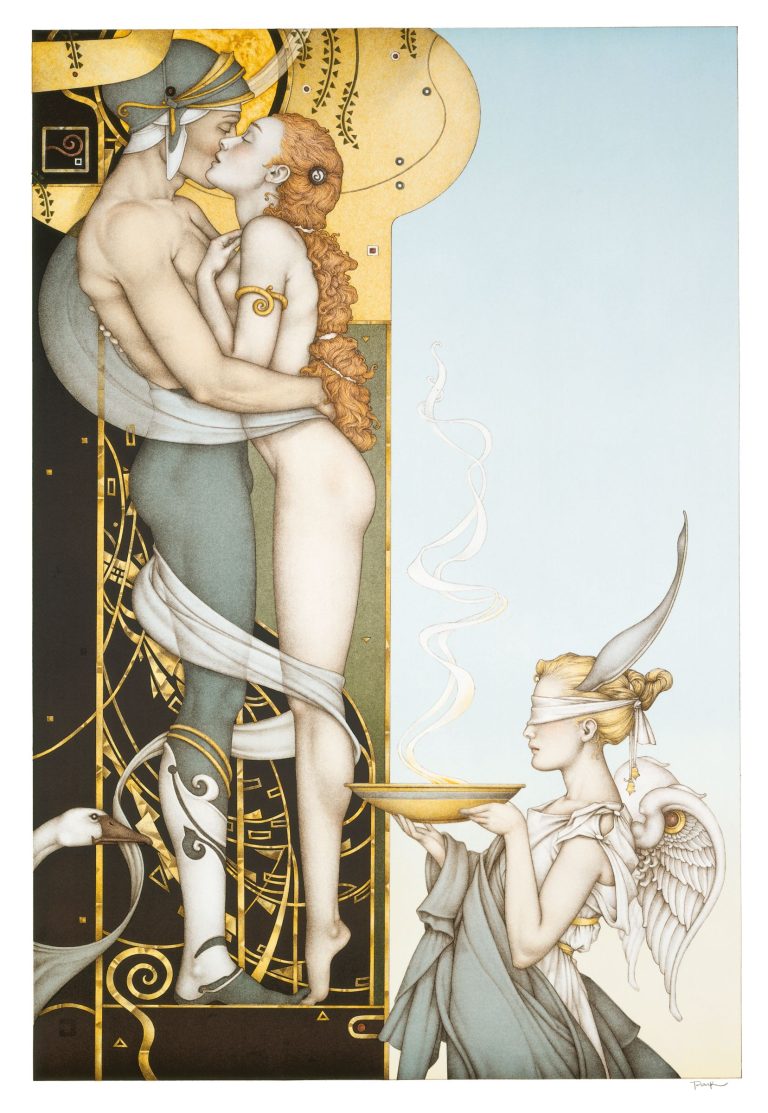

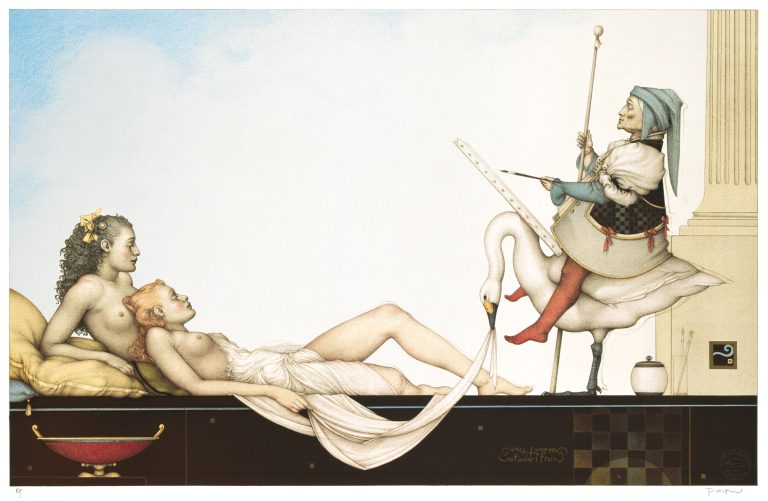

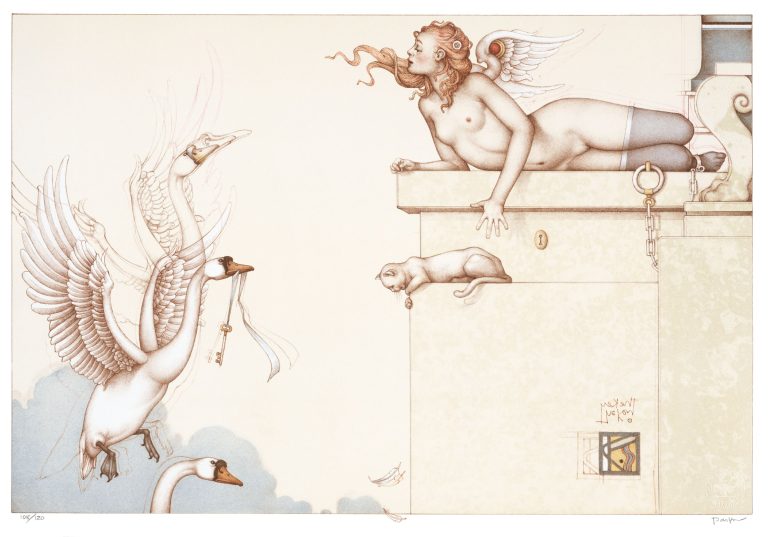

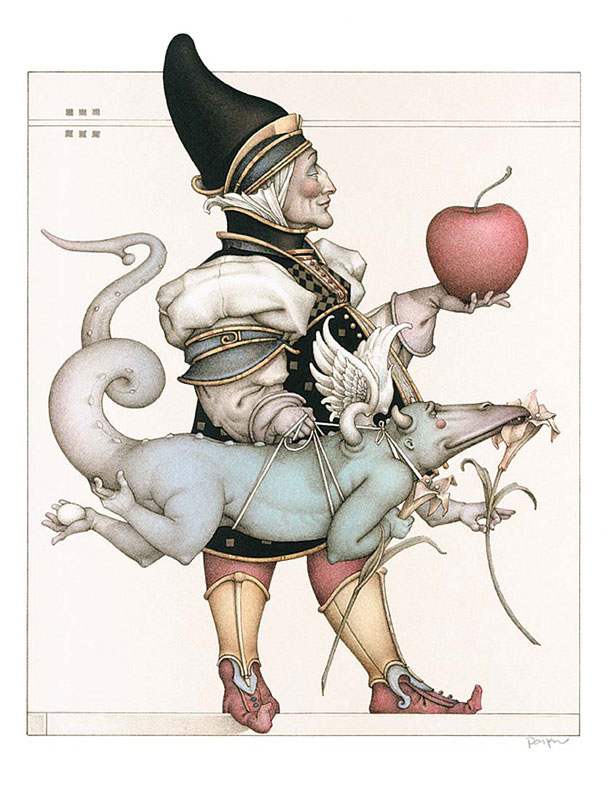

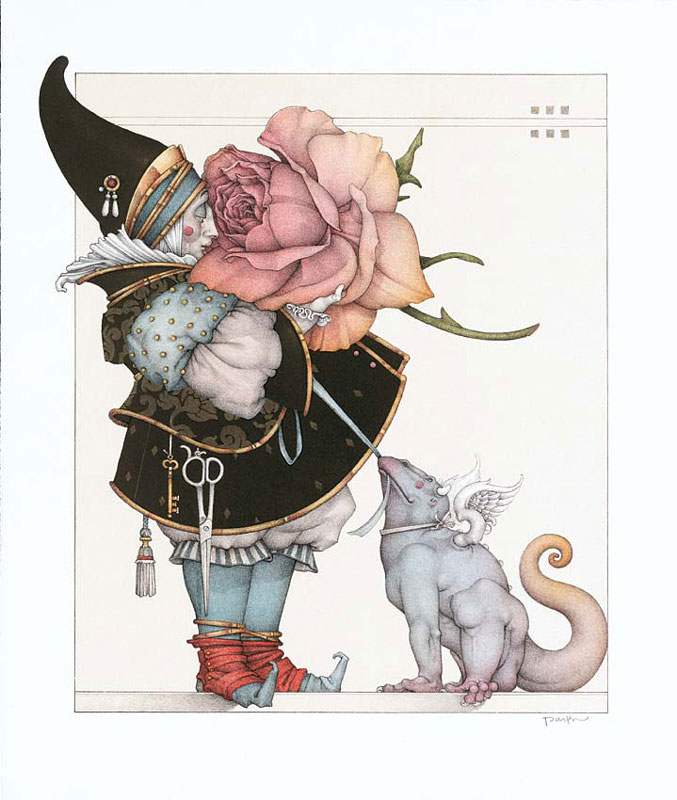

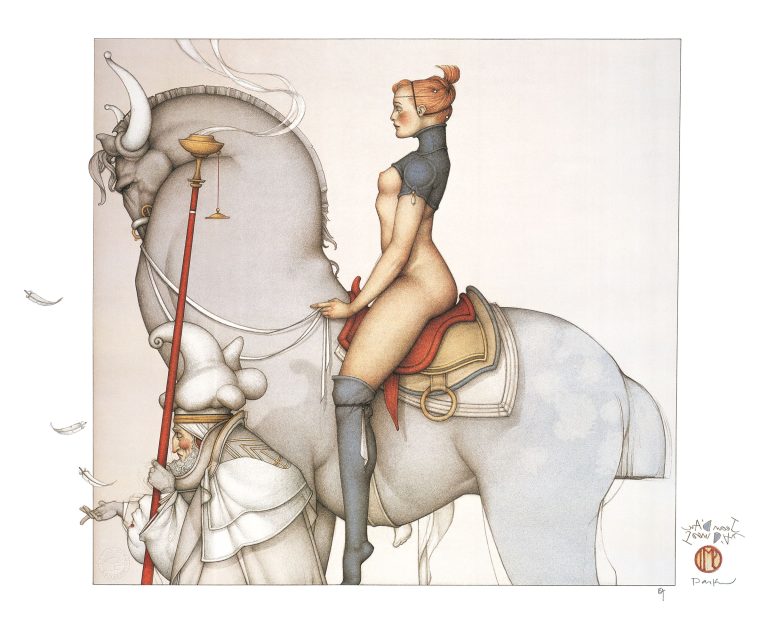

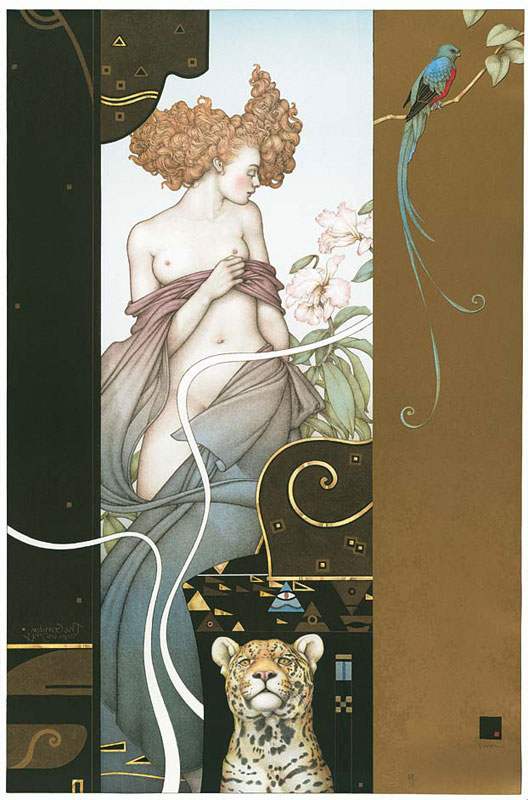

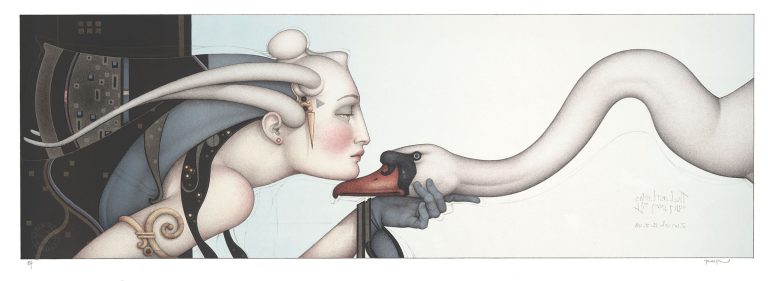

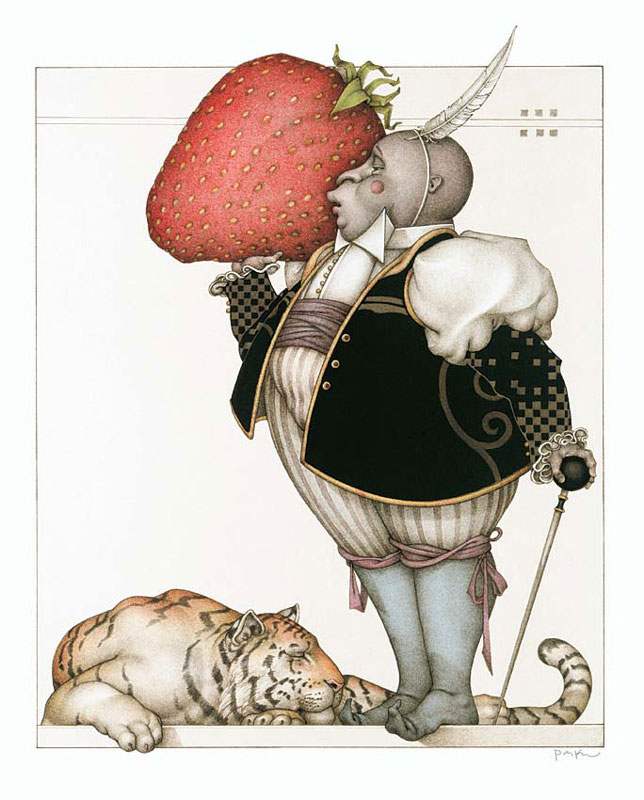

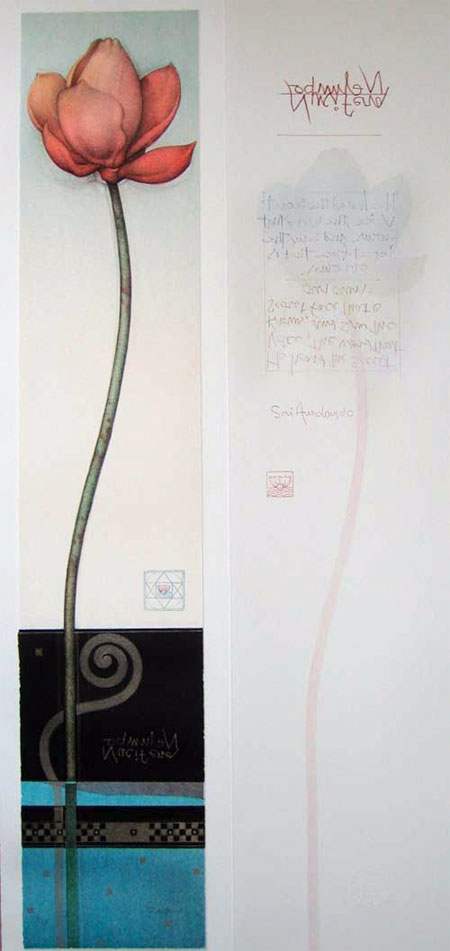

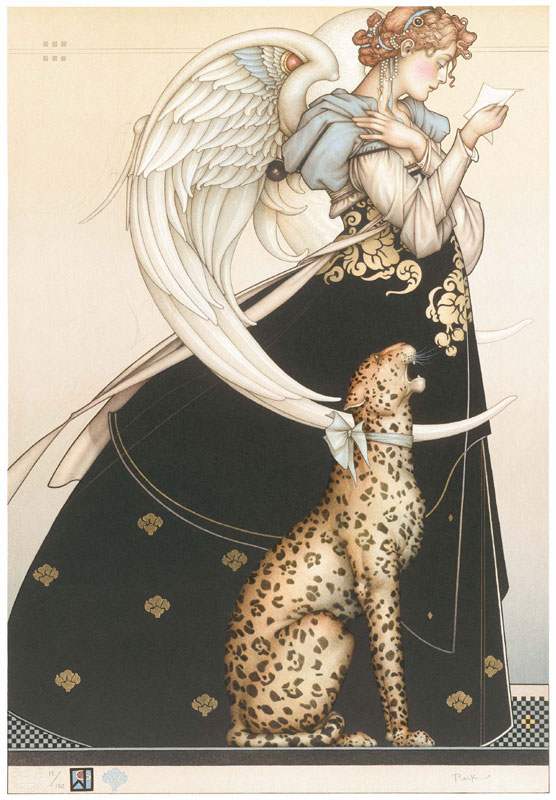

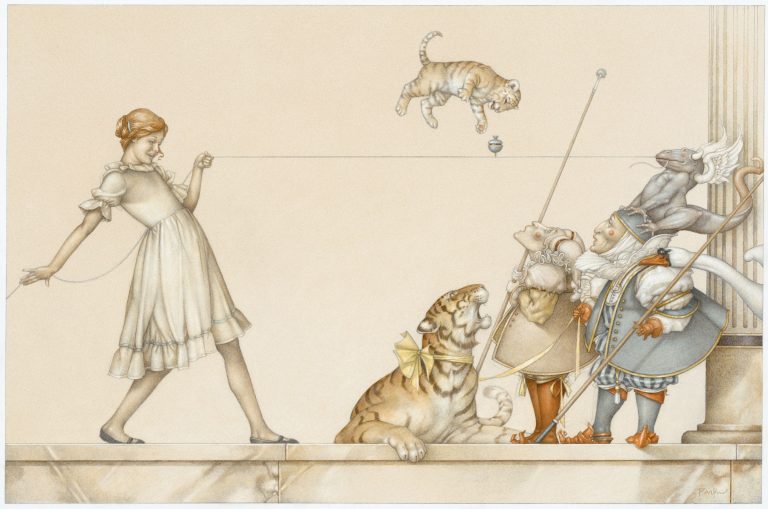

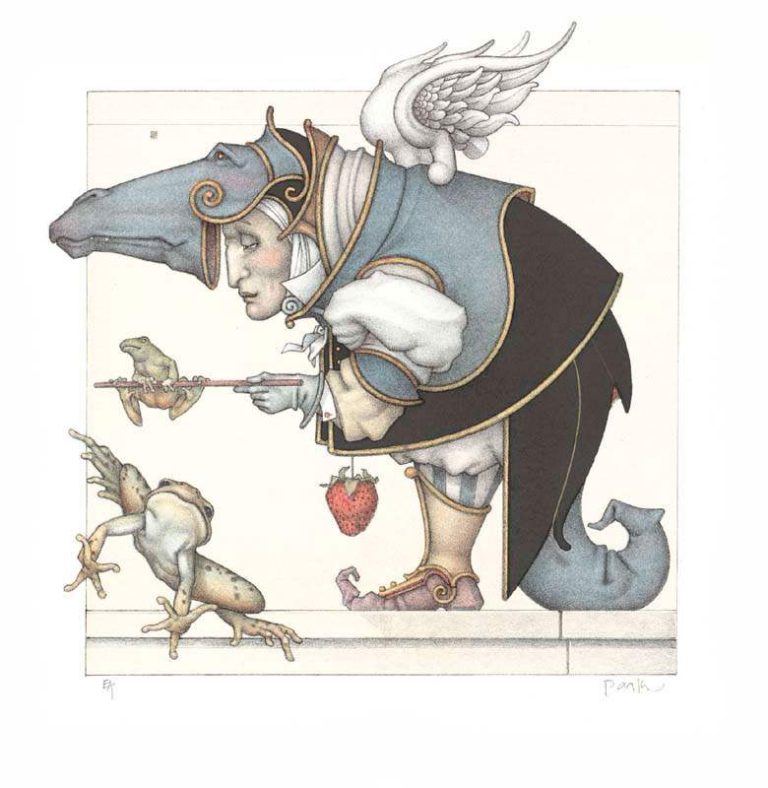

The desire to create is fundamental to the artist and the act of creation is a metaphysical experience. Painting for me has been a means to describe, record, and explore the universe around me and my relationship with it. It has been, however, my 25-year love affair with stone lithography that has helped me most to define this metaphysical journey.